ARCHIVAL WORK == DEATH WORK: self-hosting a digital archive of family video8 tapes

Azad Namazie

Content note: mentions of death & suicide.

I work in an windowless room surrounded by the endless droning of vintage computing equipment. It's like a morgue for legacy digital media and deprecated filetypes (not to get too much into my digital archivist bag, but there is literally a subdiscipline of digital preservation called digital forensics, just to make the metaphor hit a little harder). While managing the documents, images, videos of people, most of whom have since passed on, I thought to myself: all archival work is a kind of death work. And I do not just mean death in the biological sense. People die, yes, but also digital storage media fail, due to material degradation, environmental conditions, hardware malfunctions, or the predation of monopolistic service providers. When our devices fail, or we run out of reliable cloud storage options, how will we resurrect the familiar (and unfamiliar) traces of our loved ones?

This was the urgency that motivated me to self-host a digital archive of my grandfather's Video8 tapes as my own experimentation with solidarity infrastructures. These tapes document the first 10 years of my family's life (late 1980s - 1990s) in the us after forcibly migrating from Iran as asylum-seekers during the Iran-Iraq War. My grandpa is a physical media connoisseur, having ripped thousands of hours of television programming on VHS and amassing a large collection of home videotapes. I asked him if he had any home videos I could preserve for him, and he immediately offered a collection of 8 Video8 tapes.

I stopped thinking fondly or positively about nostalgia when my grandmother died in April of this year. Not only has nostalgia been weaponized by fascistic regimes to distort the past and consolidate power, but it also locks us in a state of viewing the past as an outside observer rather than an active shaper and participant. My grandmother was our family historian. She carried a lineage, our story, and a diaspora on her back. She took her own life this year when the grief and alienation of her struggles with mental health and the hyper-individualism of us society became too unbearable. In her absence, I felt insurmountable grief, rage, and betrayal. How could she do this to us? To me? Then, in the first few weeks of this course, our instructor Meghna shared an essay by Dagaaba spiritualist Sobonfu Somé on embracing grief:

"I believe the future of our world depends greatly on the manner in which we handle our grief... There are things we can do in society to help heal. We can begin by accepting our own and each other’s grief."

She goes on to describe different infrastructures we can develop to process grief: places like grief rooms and shrines in public where people can visit. What if I could develop a virtual grief room for my loved ones to view these tapes? Could archival practice be the key to unshackling my grief?

Unsurprisingly, her spirit is all over these tapes. Through my grandpa's gaze, we see her in various states of candor, reticence, domesticity, and play. After deciding to proceed with this as my final project for this course, it took a mountain of courage to finally interact with these materials and become an active participant in their digital preservation.

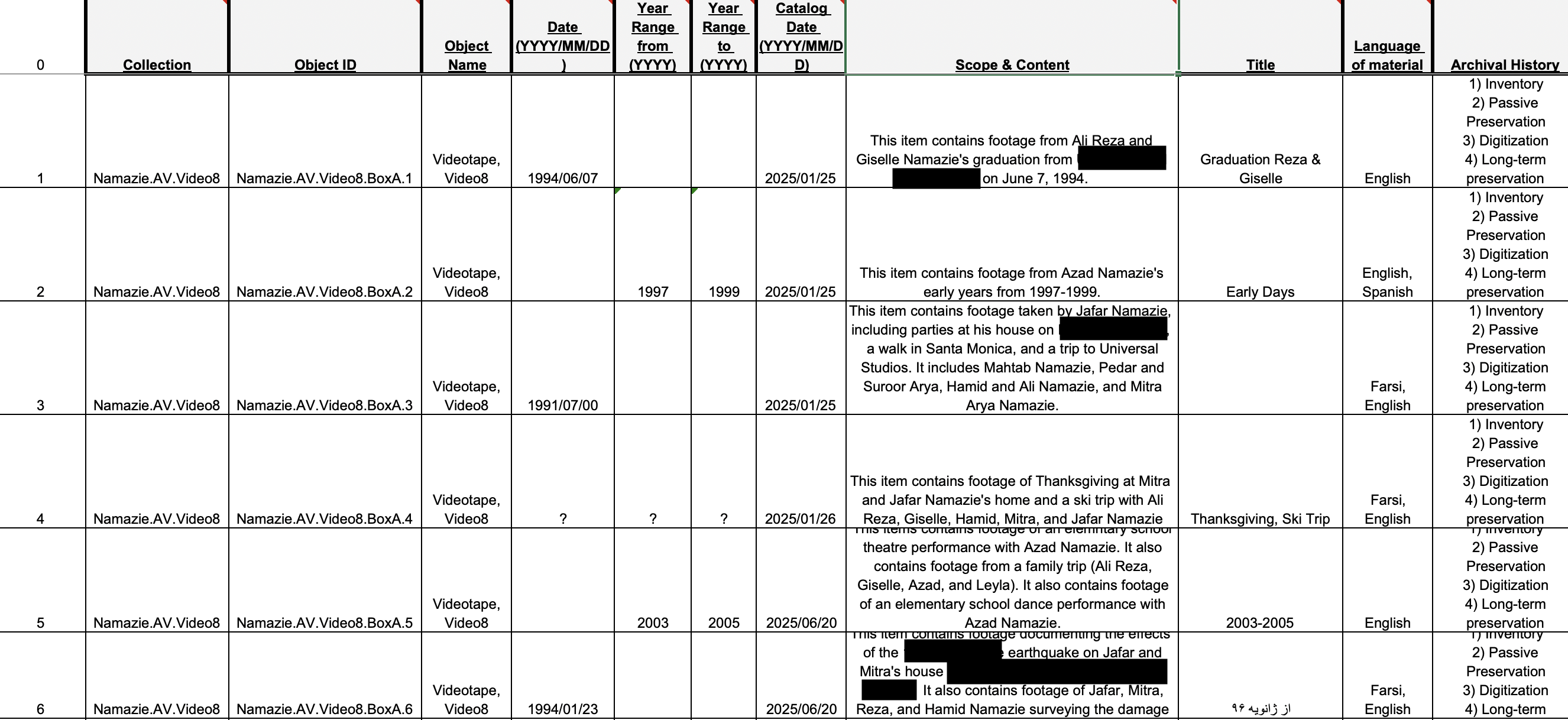

Step 1: Inventory and digitization

I started by cataloging all the tapes in a spreadsheet, assigning unique identifiers, date ranges, transcribing any container notations, and documenting other preservation actions. I then handed the tapes over to my dear friend and collaborator Jackie Forsyte, who is Technical Director at TAPE Los Angeles, a worker-owned non-profit dedicated to the preservation of tape-based media (if you are in LA, hit them up!). She graciously completed the digital transfers and loaded my hard drive with high-quality preservation .mkv files and access .mp4 files.

Step 2: Setting up the local server

I purchased a raspberry pi5 that I situated in my living room with peripherals I secured from e-waste: a monitor, a keyboard and mouse, and an assortment of legacy cables. I installed Yunohost to manage the server, set up a Tailscale tunnel, and registered my IP address with the tunnel-gateway-server. Thank you Max for your help in making this server visible to the public internet because this process was absolutely mystifying to me.

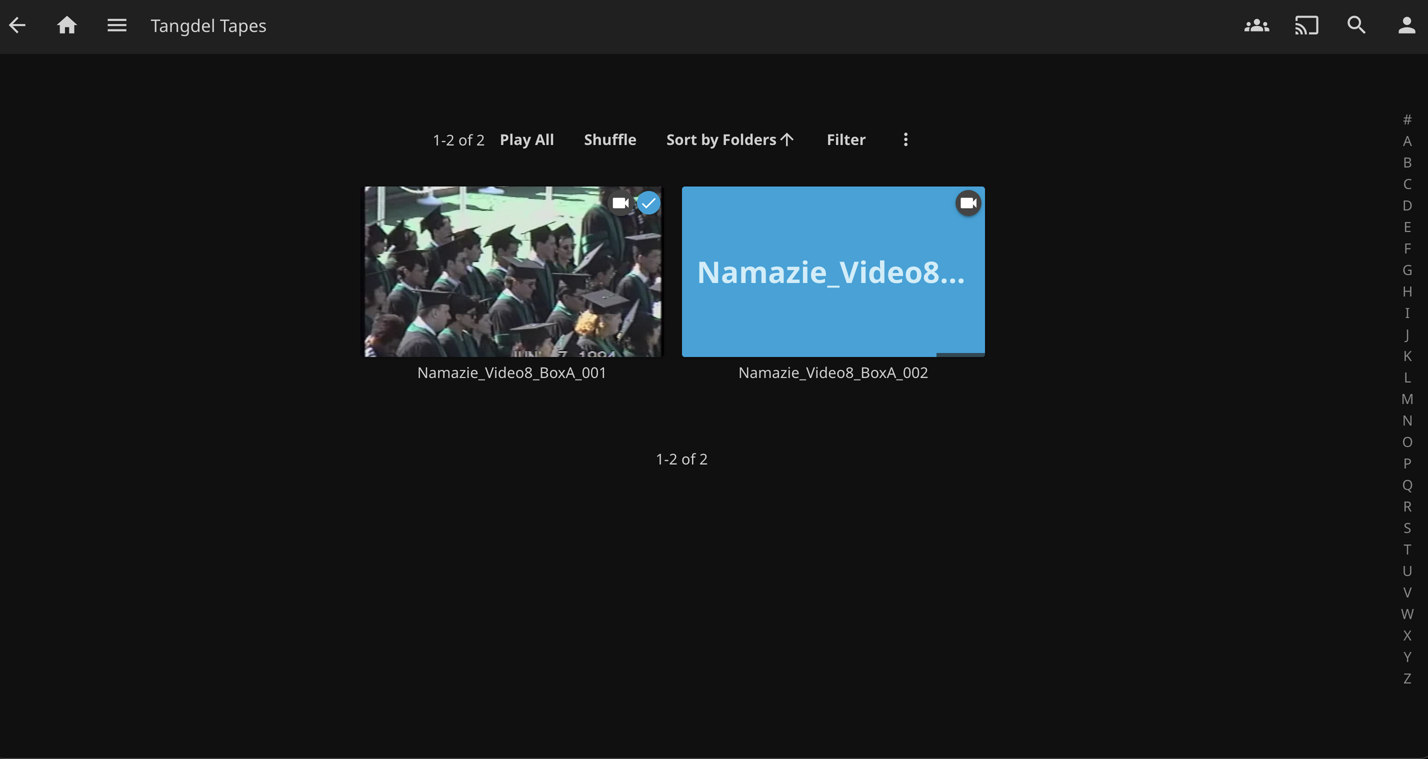

Step 3: Configuring (and troubleshooting) Jellyfin

After a chat with Meghna, I decided to download Jellyfin to host the digitized files and accompanying metadata. Jellyfin is a free and open-source media server that allows you to organize, manage, and share digital media files to networked devices. But I ran into a problem: Jellyfin would not play back the first file I loaded, returning a "fatal playback error." I checked the logs and located the following errors:

ffprobe failed - streams and format are both null

FFmpeg exited with code 243

Translation: Jellyfin asked the transcoder to inspect the video file, and the transcoder returned nothing, meaning the file could not be read. I was confused because the media file used standard codecs (H.264 + AAC), and still Jellyfin could not read or probe the file. I did some research, tested file access as the Jellyfin user, inspected the directory permissions, and confirmed that the root cause was that the file was stored in a Yunohost-managed multimedia directory, and even though the file itself was owned by Jellyfin, the parent directories were owned by root and had restrictive ACLs that prevented Jellyfin from traversing them. As a result, Jellyfin could not access the filepath, ffprobe returned no metadata, Jellyfin attempted to transcode with incomplete info, and ffmpeg crashed with the exit code 243. All of which caused the fatal playback error.

The remedy was frustratingly simple for a problem I was troubleshooting for weeks. I created a new media directory, moved the video file, updated the Jellyfin library path to point to the new location, and playback worked immediately!

Sidequest: Experimenting with ASCII character compression algorithms

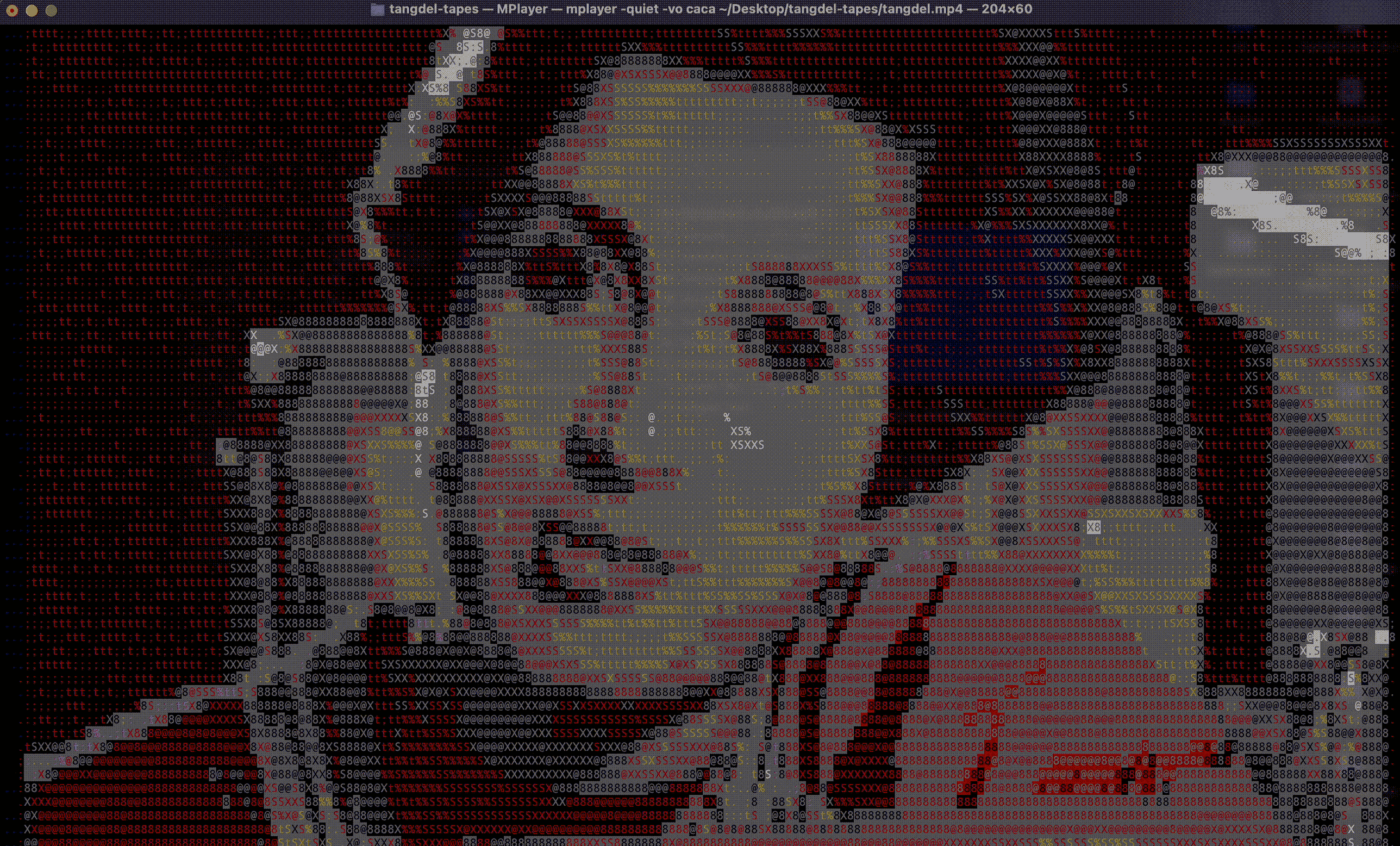

Before I went with the Jellyfin media server, I first wanted the virtual grief room to take place solely in the terminal, so I uploaded the digitized materials and inventory spreadsheet into a directory entitled tangdel-tapes (trans: nostalgia, heartsick). Then, I experimented with different ways of viewing the footage directly from my terminal via SSH. This sidequest led me to discover a compression algorithm from the libcaca graphics device driver that converts pixels to ASCII characters through a process of vector quantization. This means sampling the frame down to grayscale with less than 8bit precision, assigning a character for each value, then quantizing to a full RGB colorspace.

All you have to do is input the following script in the terminal:

DISPLAY= mplayer -quiet -vo caca /path/to/directory/input.mp4

And here is your output, directly within the terminal:

In these renderings, I could still make out her face— the gentle slope of her nose, her kind but mournful eyes— and even eerily, her joy. There is a hil malatino quote about interacting with archival specters: "haunting is not so different from loving." To behold her spirit again at the altar of my terminal felt like technological divination. Here she was, beaming at me, once again.

My sidequest with the ASCII compression algorithms reinforced some questions Meghna had posed: what is the purpose of a self-hosted media server?

To consider this question, I thought about migration as both a technical and cultural process. The tapes crossing borders; the signal crossing formats; each crossing incurs loss, but also survival. All memory degrades over time. With some filesystems, even the act of interacting with a file can permanently alter it. And corporate data infrastructure providers like Meta, Google, and Amazon care about profit, not preservation. It sounds trite, but it is really up to us to extend the conditions of our memories, beyond the limits of media failure, corporate data clouds, and empire as we know it. And the more labor we invest, the more soveriegnty we exert.

This server practice allowed me to unearth the often unseen labors that sustain our memory infrastructures and material connections to the past. There is a popular adage within the digital preservation community: no one thinks about infrastructure until it breaks. But we know that decay and rupture are an inevitable part of all lifecycles, do we not? What if we not only prepared for the ruptures, but we pursued them fervently? What if instead of running away from our grief, our rage, our dead, we created communal devotionals to materialize them into action?

Next Steps

- Upload the remaining files to the Jellyfin media library.

- Update the exif metadata to include accurate locations, date ranges, and other content notes.

- Customize the CSS to match the tone of a virtual grief room.

- Share the public link with my family.

༘⋆📼˚ ༘ ೀ⋆。˚༘⋆💾˚ ༘ ೀ⋆。˚༘⋆ᯤ˚ ༘ ೀ⋆。˚༘⋆👨🏽💻˚ ༘ ೀ⋆↻ ◁ || ▷ ↺ ೀ⋆。˚༘

About the author

Azad Namazie is a poet, performance artist, and digital archivist from Los Angeles, CA. They create websites, archives, and multimedia performances for live and internet audiences.